This post is part of a series.

Background: This Internet, on the Ground

Part 1. Governable internets

Part 2. How governance could be

Part 3. What are DAOs?

Part 4. An internet of DAOs

Part 5. Identity bureaus

→ Part 6. But can it govern?

Part 7. Pockets of liberation

The next revolution

The cultural phenomenon that is web3 revolves around two, fundamentally different groups. First, there are people who've found a technology and want to make a revolution in markets. (Some advice for them here).

Second, there are people who want a revolution in society, and seek the best available methods for doing so. If you accept the premise (as I do) that a meaningfully democratic society is desirable, and you find yourself convinced by thinkers like Bookchin and experiments like Rojava’s, the question becomes: how do we create such a society in the West? Where do we begin?

My thesis is that web3 technologies, tactically deployed, are the most effective route available to grassroots direct democracy in today’s West. This is due both to their technical affordances and to the fact that “crypto” has solidified as the dominant narrative of escape from neoliberal governance.

As I argued last time, the missing link between web3’s general technical affordances and its political use to direct democracy is the identity bureau. If constructed carefully, identity bureaus could facilitate a nonviolent transition to a more meaningfully democratic society. AS DAOs built on top of identity bureaus could produce radically non-geographic states, interlinked into partially overlapping “blocs.”

But can it govern?

Imagine: a neighborhood—perhaps yours—assembles an identity bureau and distributes identity cards to community members as broadly as it can. Each identity receives some non-transferrable governance tokens and some fungible local currency.

The bureau then organizes popular assemblies. This on-the-ground organizing would take months if not years, forming a politically activated polis participating in local governance over local affairs, neighborhood-by-neighborhood. (How popular assemblies form and function is well-covered, both in theory and practice, elsewhere).

Now—can it govern?

In this post, I’ll show you how popular assemblies built from identity bureaus and AS DAOs could replicate the governmental functions that democratic thinkers care about: legislatures, courts, property rights, management of the commons, and so on.

My job is to convince you that an AS DAO, given form by an identity bureau, could accommodate these functions. For some, it may exceed traditional structures in efficiency; in others, it may act at parity. My aim is not to convince you that DAOs will “revolutionize” each (or any) of these institutions—though they may. Rather, it is to convince you that there is no governmental function to which the formulation I’ve described is outright incompatible.

Elections

Elections are central to my claim that popular assemblies and DAOs could co-exist; that the latter could represent the former. Any claim of geographically fluid democratic blocs necessitates trustworthy elections.

There’s some great work on online voting. Jefferson et al (2004) analyze a truly atrocious design for an online voting system. The topic has enjoyed rigorous treatment over the years.

In the context of a DAO, the integrity1 of an election’s results reduces to two assumptions. First, there should be a one-to-one mapping between identities and natural-born persons. If someone can produce fake identities, they can manipulate the election’s results. Second, each individual should possess their private key—their identity card, in our case. If an individual is willing to lend their identity card and PIN out, or if they get their identity card and PIN stolen, their vote can be stolen.

The identity bureau provides the former assurance. We are left with questions about the latter. That is: we are left with the same threat model as in vote-by-mail in the U.S. If someone comes around and offers you cash for your ballot, or you give your ballot to them, a mail-in vote would be similarly compromised. In fact, we are slightly better off than in the mail-in case: identity cards require a PIN to use, whereas vote-by-mail ballots only require a signature. The former is secret, the latter is given freely. And people ought to be more careful with their identity cards than with their ballots. If an attacker takes someone’s identity card and PIN, they could escalate privilege to all manner of services. Ballots only let an attacker steal one’s vote.

Elections in DAOs also prevent capricious non-counting of ballots (e.g., due to a purported “signature mismatch”). A voter registered2 at the time a proposal is launched will have their vote counted.

Overall, elections in DAOs whose identities derive from identity bureaus are at least as secure in theory as those done with voter rolls and mail-in voting, and at least as auditable. Needless to say, they are more auditable than elections over privatized computer voting machines, which are largely closed-source and uninspectable when push comes to shove.

Legislature

Codified law is the central institution of any well-ordered society. Laws are ledgers: rules, which change over time, via well-specified processes. The processes by which rule-making can change are similarly well-specified.

The sorts of processes legislatures employ—quorum, voting thresholds, and so on—are well-captured by already-existing DAOs. Popular assemblies can create legislative bodies, or elect representatives to form or sit on legislative bodies that manage affairs across various popular assemblies. DAOs would not inhibit these activities, and may even provide some marginal improvements to their efficiency.3

Courts

Smart contracts cannot and should not “automate” the court system, whatever such a term might mean. It is human judgment’s role in mediating ambiguous situations that makes courts powerful and useful as a tool for adjudicating disputes.

That said, DAOs will not hinder courts either. Like legislatures, they may add some marginal efficiencies. Decisions made in courts can be recorded on-chain as a matter of public record keeping. Court stenographers can enter court records in on-chain formats. In more sophisticated formulations, juror selection could be performed by smart contracts, with ZK proofs protecting the identities of the jurors assigned to particular cases.

Of course, the exact risk/reward tradeoffs of such on-chain “optimizations” should be pondered carefully. Courts have worked well enough for hundreds of years and may not need any further disruption. The German word Verschlimmbesserung—an improvement that makes things worse—comes to mind.

Property ownership

Ownership over property, particularly public goods, is a natural case for public ledgers. Property tax records in the U.S. are functionally ledgers, albeit a piecemeal kind built on top of a pre-digital system of identity.4 In a DAO, properties could be mapped to identities in a straightforward way for the purposes of sales, transfers, and taxes. How similar systems could be used to manage the commons has been discussed elsewhere at some length; it’s a fruitful area for research.

Taxes

With a local currency, taxation is simple. Contrary to popular narratives of web3 producing "ungovernable" money, possession over which is cryptographically assured until the end of time, DAOs can govern money however they like, including repossessing it via transaction fees (sales tax, VAT), or on a set schedule (property tax, income tax).5 Combined with robust records of property ownership, regimes like Georgism could see a resurgence in such a system.

Welfare and UBI

Similarly, DAOs can print or redistribute money to provision any sort of welfare scheme. Universal basic income (UBI) is a straightforward case: a regularly-recurring airdrop can be guaranteed to all identity-wallet-citizens.

Means-based welfare, while always trickier, could at least build off of a robust identity system—one linked to other relevant ledgers like property ownership. These linkages could reduce the administrative complexity of running a means-testing system. (I can imagine, for example, a public ledger of births, deaths, and civic partnerships that provisions cash transfer to parents of young children). Building on top of public records keeping, which popular governance weighs privacy against public benefit, citizens can scale welfare to taste.

Public works

Taxation can similarly mobilize labor and materials for public works: roads, bridges, schools, medical care.6

Medical care is an interesting example. It requires not only mobilization of resources and talent, but also meticulous record-keeping with privacy top-of-mind. This case would be an interesting one to noodle through further.

Schools present another interesting case. Parental input must be weighed against other governance goals. Resources, teachers, student privacy, and more collide.

Yet these lofty public works are meant only to stimulate the imagination about the possibilities of a DAO-based popular assembly that can mobilize resources to a shared purpose. Public works could be as straightforward as granting money to artists—or rewarding anyone else who performs a civically useful task, proactively or retroactively.

Rough contours

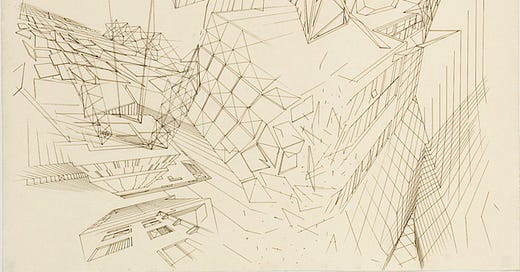

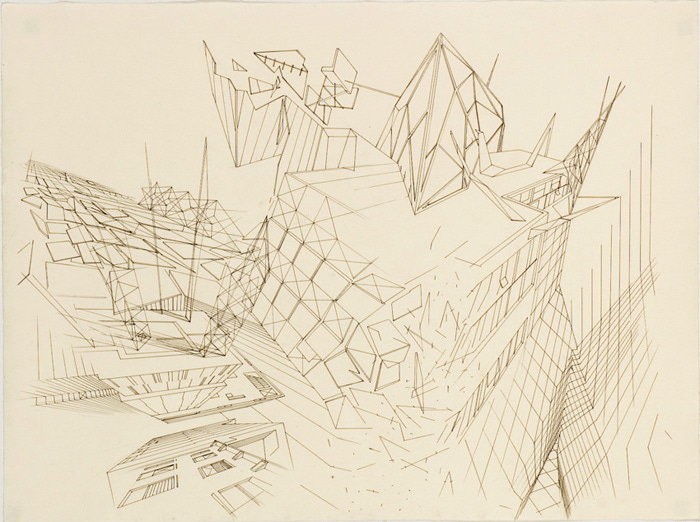

These proposals are sketchier than what I usually put on the page. They're meant to stimulate an appetite for further work, a hunger to understand the ins and outs of these cases.

The upsides to a locally-governed system are great: a meaningfully democratic society, built from the grassroots, and with direct governance over its internet—its means of provisioning global data trade. Before we talk about the downsides, however, let’s return briefly to blocs.

Securitization

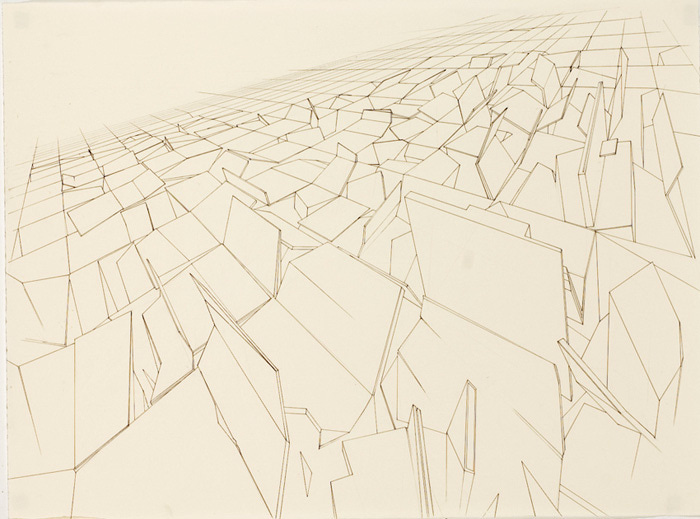

Popular assemblies are of little use alone. They are strongest and most flexible when they join together into confederations. The exact nature of these confederations can be flexible and emergent. They may produce complex state-like structures such as parliaments. Yet the authority of any structure derives ultimately from localities, whose revokable consent always and inalienably flows up.7

These blocs, as formulated around AS DAOs, may be flexible in their geographic form. They may partially overlap with other blocs. They may be geographically non-contiguous, connecting blocs across the world that align ideologically or otherwise.

As I mentioned in a previous post, blocs represent logical fiefdoms, whose rules, standards, formats, and laws structure that bloc’s interoperability with the outside world. Within logical blocs, shared data governance regimes and identity systems could enable free movement of people, shared securitization.

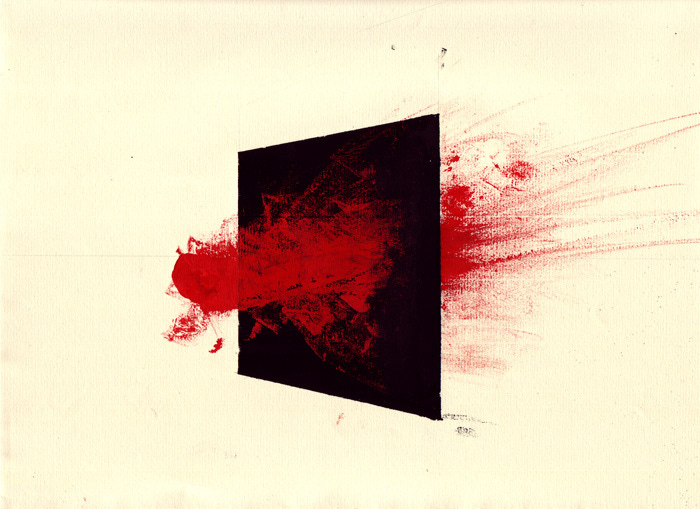

The bear’s case

I’ll wrap up this series next time with a discussion on why this scheme might not work. Why it might be dangerous to even attempt.

I'll convince you that democratic experimentation is worth its risks, even if its successes are only ever partial. Pockets of liberation can exist, I'll argue, and the proposal I've laid out over the past weeks is the most plausible path available to producing them in the current political moment in the West.

Until then.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Rachel Wesen and Nils Gilman for the conversations.

The availability of the election system to make those results known, or to cast those votes, is a separate matter that has more to do with the validator set and its resistance to DDoS attacks, a topic for another time.

The confidentiality of the election system (namely, its ability to assure that votes are cast in secret) is an interesting cryptographic problem under active investigation in DAO DAO.

That is, a wallet with staked governance tokens.

While it’s easy to oversell their capacity, modern consensus algorithms can provide evolutionary advances in the efficiency of parliamentary systems, particularly during moments of “breakdown.” If you didn’t see it live, watch the election certification vote on January 6. It’s effectively a human BFT. Someone stands up, dishonestly refuses to certify the vote, and everyone has to sit and listen to whatever the person has to say. Then everyone has to vote them down—effectively, to sign the block without their transaction. This process is the sort of thing Tendermint automates. The whole failure-to-certify debacle would have been much faster and much quieter—much less of a spectacle if voting had occurred via a modern consensus protocol.

In the U.S., Social Security Numbers are used as both usernames and passwords. To say “pre-digital” is not to say “obsolete by default,” but identity systems that predate modern security analysis have run into problems.

In Juno, the community pool is replenished through taxation on validators. In fact, there was a discussion at one point about whether a scammer should have their tokens expropriated to the pool (see footnotes of this post). The moral here is that web3 technologies can allow for arbitrary logics of token production and transfer, not just the libertarian logic of permanent and inalienable private ownership.

Ben Bartlett, Vice Mayor of the City of Berkeley, floated the concept of using web3 for municipal bonds and UBI in 2018.

Local units need not be parochial. Rather, the mechanism by which they become globally interlinked remains in the hands of the local polis. The result is a geographic flexibility to the ‘regionality’ of globalization; a fine-grained and geographically non-exclusive model of sovereignty, more flexible and dynamic than nation-states could afford.