Who runs the Internet?

Wikipedia says,

No one person, company, organization or government runs the Internet.

In theory, this is true. In practice, a few US-based companies dominate the services core to the Internet’s functioning.

Inspired by the Internet Society’s Internet Way of Networking principles, Konstantinos Komaitis, Carl Gahnberg, Andrei Robachevsky, Mat Ford and I were interested in threats to the Internet’s core principle of decentralization: the idea, summarized above by Wikipedia, that no one party should have too much power over the Internet.

We looked at companies who provided four, key types of services core to the Internet’s functioning: web hosting, data centers, DNS servers, and SSL certificate authorities. We got the marketshare for each company from W3Techs, who query millions of websites every day to determine (among other things) who provides these services for which websites.

At the level of service providers, it is ostensibly true that no one company dominates the Internet. Even the mighty Amazon “only” controls 5.7% of their marketshare. That’s a lot, but it’s far from domination.

However, at the level of nations, the picture isn’t so rosy.

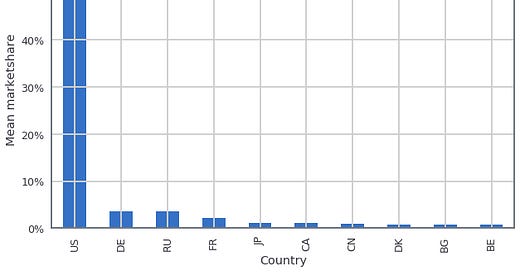

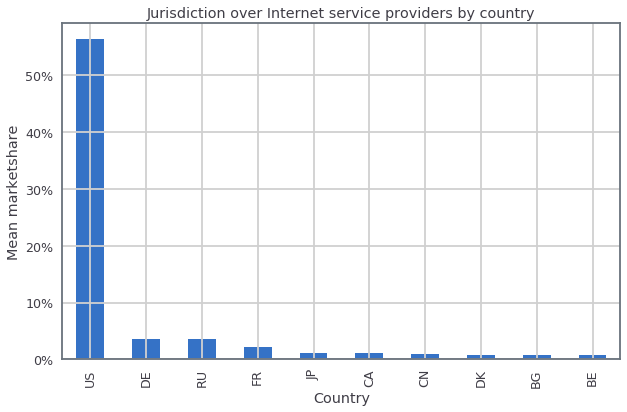

For each service provider, we labeled the legal jurisdiction it resides in [1]. Remember, we're not interested where these companies provide services geographically. We're interested in what jurisdictional power can meaningfully exert influence over these service providers; in other words, how much of the Internet each country dominates through its jurisdiction.

As you can see, US service providers dominate. Companies in US jurisdiction account for more than 50% of the marketshare in these core Internet services.

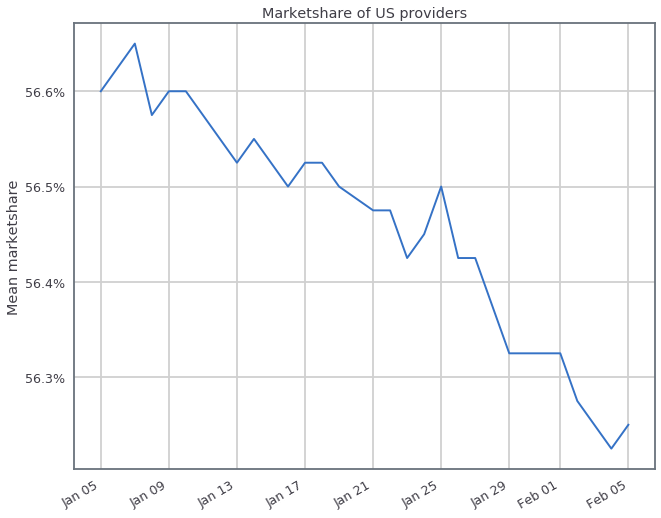

However, the marketshare of US companies have steadily declined over the one month we’ve been watching. It’s a short timescale, but a fairly steady decline.

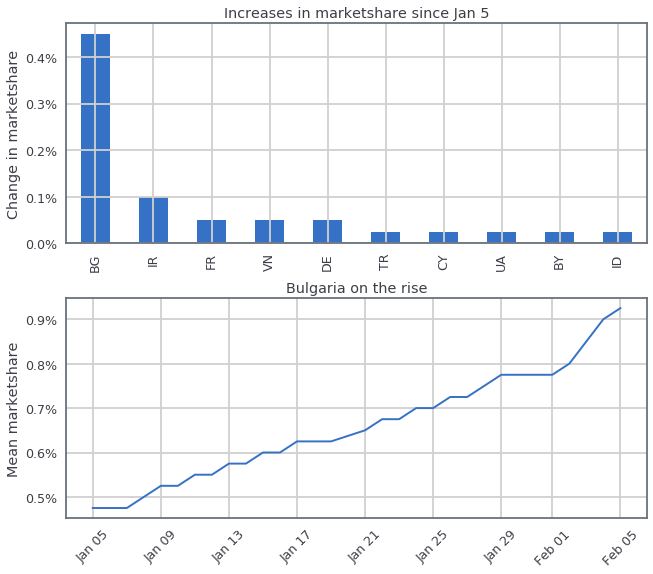

Who's been gaining? Europe, mostly. Bulgaria especially.

Why this trend away from the US? And why Bulgaria? Well, I have some guesses, and I'll share them later once I have some better data. But more on that in a future post.

National power & the Internet

Who runs the Internet? Well, in the sense of “who has jurisdiction over the companies that provision core Internet services,” the US sure comes close. If the US doesn’t run the Internet, it certainly dominates the provision of its core functionality.

The point is not to shame the US. The point is that the Internet does not, and has never floated freely from national politics. Powerful countries have power on the Internet, too. In the data we have here, that expresses itself as market dominance. It’s not the only way countries exert their national power online, and I’m sure I’ll talk about many others in the near future. But it is one way that nations can exert their political influence over the Internet. We have yet to see the US really flex this power. (Sure, Amazon kicked Parler off of AWS services. But that was ostensibly their own decision.) If tech companies do see some increased regulation, we could see significant ripples across the global Internet, perhaps in the form of content disappearing.

But again, this isn’t about the US per se. The US may not always be the country on top. I wouldn’t draw too much from our short-term data on US decline—we’re working on collecting historical data to get more context—but the fact that those data fluctuate at all does indicate that things change. Markets change. Countries rise and fall in power. The question isn’t so much about how much we like today’s Internet. It’s about how much we like the fact that the Internet’s core services can be dominated by a particular jurisdiction.

Our question then becomes: what does a more equitable Internet look like? How can we quantify the equity—or lack of equity—in Internet dominance, and how can we use that measurement to determine whether we’re getting closer or further away?

More on that next time.

Thanks for the Internet Society for funding this work.

In other news…

Steve Weber took me to task on last week’s post on the central bank analogy, particularly my assertion that an error on the level of Australia’s misfire in regulating Google “would never be tolerated” by a central bank:

Uh.. talk to someone at the ECB in 2010, when they prematurely raised rates and pushed most of the Euro area back into recession. Talk to Janet Yellen and she’ll tell you that at least half the post war recessions in the US were worse than they needed to be because the Fed was operating with an overly aggressive anti-inflation bias left over from the 70s oil shock period.

Point is simply to say, these kinds of errors are the norm not the exception. Central bankers have more theory at their disposal to guide their actions, but the theory turns out quite often to be wrong — and that might even be worse than flying blind.

Just look at the switch between 2009 and now. Despite the fact that 15 months ago any reputable monetary economist would have laughed at someone spouting what was called New Monetary Theory, the Fed is now more or less acting as if it were true.

I think the fundamental problems are, like with internet regulation, dual:

1. Lack of empirical feedback in a massively complex system — it’s hard to learn from experience because you don’t really know what the impact of your intervention was, relative to other causes

2. Disagreement about the objective function (sometimes hidden in #1): Just like there are inflation hawks and doves in central banks, internet regulators have different views of where they want the system to ‘land’. This isn’t always transparent, but when you think about it, it’s pretty obvious.

So, you have in both cases, different preferences, weak theory, and lack of evidence. A perfect recipe for continuing errors.

I don’t disagree, and I appreciate the check. I’d still argue that central banks are, on balance, more effective with data than without it. And Internet regulators likely would be, too.

If nothing else, data forces us to commit to particular theories. They may be wrong, and they may cause misfires, but at least these misfires allow us to revise our theories. The fact that Steve is able to refer to “an overly aggressive anti-inflation bias” represents a level of theoretical refinement miles ahead of where Internet regulators are today.

Once Janet Yellen is done being treasury secretary or whatever, perhaps we can ask her about it.

Footnotes:

1 Lily Bhattacharjee heroically labeled all 238 service providers in a single weekend. Mariah Stennis checked her work and found no errors.